North Vietnam

HONKIN' HANOIWe arrived in Vietnam more than a little nervous. For one thing, Vietnamese is a tonal language, which means that each syllable can be pronounced six different ways, each having a different meaning. We were afraid we would be unable to communicate. We weren't sure about how safe we would be, or how welcomed.

Luckily, we were quickly surprised by how nice it is here. We are still unable to communicate in Vietnamese beyond "xin chao" (hello), but a lot of people speak enough English that we can get by. And bargaining can be done with just fingers or paper and pen.

What was the most surprising was how pretty it is here. Even in central Hanoi, the streets have a pretty movie-set feel. At night, the labyrinthine streets of the Old Quarter are well-lit and full of locals buying, selling, and eating. There is a lake between the Old Quarter and the French Quarter that is surrounded by a band of park. After dark on weekend nights, the benches are filled with starry-eyed teenage couples whispering to each other.

We met these kids in a park-

they liked the pictures in our booksLike any city, Hanoi has its irritations as well, most notably the vigour and persistence with which its residents honk their horns. The honking is omni-present, and mingles with the cries of cyclo (becak) drivers and music and news broadcast over government loudspeakers.

Maybe the most intriguing thing about Hanoi are the stores in the Old Quarter. With few exceptions, each store sells only one kind of item. And most streets specialize in something, too. This goes to extremes -- we saw a street with several stores selling only stovepipes. Every kind of merchandise is subject to this specialization: all manner of clothes and underwear, hats, shoes, doorknobs, gravestones, tea, flowers, silver, stickers, etc. It's the ultimate way to comparison-shop.

Something else that struck me is how well-dressed the Vietnamese are. In the city, that's not much of a surprise, but as we ventured out into the countryside, we saw even poor fishermen wearing spotlessly clean button-down shirts and slacks.

~ * ~ PERFUME PAGODA

Our first trip out of the city was a day trip to the Perfume Pagoda. It was on this trip when we first began to suspect just how beautiful the Vietnamese landscape is.

After a bus ride, our tour group was packed into a few small rowboats for an hour-long paddle upriver. The paddling was done by petite, smiling Vietnamese women who handled what must have been a very heavy load with ease.

Boats waiting for tourists

Packed in like sardines

When we disembarked, the next stage was an hour-long hike up a mountain, using stone steps that looked like they'd been there a while. It was nothing like the hiking Steve and I were used to, because eager vendors lined the entire route, hawking cold drinks and places to sit and rest.

Looking down into the cave

Looking up from the cave

When we finally reached the top, we were surprised to find not a pagoda exactly, but a huge cave that was considered a natural pagoda. It resembled the mouth of a dragon, complete with uvula. Inside, a crowd of Buddhists and tourists walked among candles, admiring the rock formations, lighting incense and praying.

The way back was similar but in a more downhill way. We counted our blessings that it was not raining, because the rock steps would be very slippery when wet. Before getting back in the boats, we had noodles and rice for lunch and visited the Kitchen Pagoda, a more traditional pagoda nearby.

Then, we retraced our steps back to the boats, and then took the bus back to Hanoi.

The smile of one of the boatwomen

~ * ~ BEAUTIFUL HA LONG BAY

Let me just get it over with and say that Ha Long Bay is one of the most beautiful places I have ever been. Even more beautiful than the mighty Milford Sound.

It is kind of similar to Milford Sound in that there are forested rocks jutting steeply out of the water. But unlike Milford, this goes on for miles and miles in a bay full of islands. Steve and I went on a three-day cruise tour, spending one night on the boat and one night in a small town, Cat Ba Town, on the biggest island.

The harbour in Cat Ba TownOur boat was remarkably worn-out underneath. The wooden hull looked like it was rotting, and there was dirt around the edges. But the owners of the boat had done a pretty good job at putting a nice veneer on the boat; the curtains and bedding were okay, the inside floors were tiled, and the decks freshly painted.

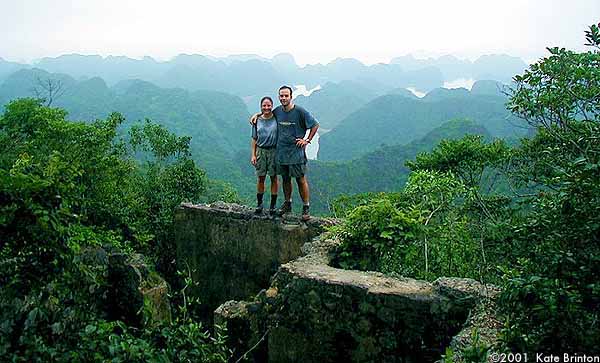

Basically, we spent most of our time cruising around the bay, with a stop on the second day to walk to a village on Cat Ba island and hike to the island's highest point. The hike was a 45-minute scramble straight up a slope, but was rewarded with a gorgeous view of Ha Long Bay.

Us on top of Cat Ba islandBut the best part of the trip was the time just spent sliding past the profusion of islands in the bay. It was foggy during our whole visit, which brought a dreamy feel to the place. Aside from the occasional fishing boat or floating house, we were alone on the water. It almost seemed as if the ghostly islands were lining up to glide by us one at a time. In the distance, the islands stood numerous like teeth. Up close, they became greener and intrigued us with the promise of dark caves.

Since we had so much time in the bay, we were able to relax instead of feeling like we had to concentrate on the view all the time. We could read, and look up occasionally to be surprised by the beauty all over again.

~ * ~ SA PA: The Cloud Yard

We took a train to the north of Vietnam, so far north that we could see China across the river. Then, we piled in a mini-bus with too many other people and ascended into the mountains to visit Sa Pa.

Sa Pa is a town nestled a mile high, across from Vietnam's highest mountain, Fan Si Pan. (I would be remiss here if I didn't mention the multitude of "fancy pants" jokes that mountain spawned.) The view down into the valley from Sa Pa is full of terraced rice fields and man-made ponds.

In Sa Pa, I got to experience two fantasies.First was the fantasy of winter. I missed winter this year, spending what is usually the winter months in New Zealand and Australia, where it was summer. I couldn't remember the last time I was cold. But Sa Pa is at a high elevation, and so the nights can be chilly. Steve and I walked around the streets at night, revelling in the chill; me bundled in my fleece coat, Steve wearing two shirts. We had a fireplace in our hotel room, and actually used it one night. It was like one magical Christmas-season day.

The other fantasy was my lifelong desire to fly through the clouds. Since I was young, I've always wanted to be outside the plane when it flew through the clouds. I wanted the cool wisps of the cloud to surround me. Despite a few near-miss attempts while paragliding, I had never come closer than a garden-variety fog.

Our view at first

Our view on the third day

In Sa Pa, it was different. Clouds, real and thick, congregate among the mountains and play hide-and-seek with Sa Pa. Our hotel room directly faced Fan Si Pan, but it wasn't until our third day that we even saw the mountain. Being up so high, the clouds move fast, much faster than they ever seem to move at sea level. They reach their tendrils around walls, and zip through the street, obscuring adjacent buildings from view. Once or twice, I was lucky enough to be standing somewhere and the clouds would whip up from below and flow around me, through my fingers, and onward.( The term "Cloud Yard" is borrowed from a park in Sa Pa. )

~ * ~ REBEL WITHOUT A HAT

Steve and I had just finished a discussion about the clothes worn by the hill tribes. There are a multitude of small tribes that live in the north of Vietnam that are ethnically different from the Vietnamese. These "minorities", as they are called by the Vietnamese, live in rural villages and make their living through agriculture and selling their traditional crafts to tourists. The most striking thing about the hill tribes is their costume. Each tribe has a distinct and colorful outfit that is worn by everyone. The men and the women have a different variation, but it is easy to tell the tribes apart by their clothes.

Two H'mong girlsI had wondered aloud to Steve if it ever occurred to anyone in the tribe to question their "uniform." Didn't anyone want to look different? The answer seemed to be no. We concluded that maybe the force of tradition or something unknown was stronger in the hill tribes.

We were hiking down the mountain from Sa Pa to visit some H'mong villages. As we turned off the main road, we were joined by three girls. They began with the usual question: "Where you from?" By now, we weren't surprised to hear English. We had found that many hill tribe people spoke better English than most Vietnamese, and the children were the most proficient.

So we wandered down a dirt trail and made conversation with the girls. One girl left us shortly, but the others spent the afternoon showing us around. Their names were La and Tu. La was the outspoken one who divided her time between getting to know us and giggling in H'mong with Tu.

As we walked, we noticed that La wasn't wearing the traditional H'mong hat. Steve asked her about it. She replied that her parents had made her one, but she "didn't like it." In that day and the next, we never saw her in the hat. And she was the only H'mong female (besides the babies) we saw without one in our time in Sa Pa. We had found a rebel!

La is the one without a hatThis streak of independent thought warmed me to La, although there was plenty about her that was remarkable. She was quick and intelligent, with a fairly good grasp of English. For a nine-year-old girl, she had an uncanny sense of restraint and presence. In contrast with some of the young boys who ran up to us and yelled "pay! pay!" (asking for money), La would more often politely refuse a gift than accept.

Rice paddies in La's villageShe (with Tu in tow) showed us her village and her house, then walked another 4 kilometers with us among terraced rice paddies to show us her school in the next village. She never asked us for anything in return for the tour, so we bought some of her merchandise. (Every H'mong girl carries around jewelry and embroidered things to sell to tourists. We think they probably account for a large percentage of a family's income.) Steve bought a bracelet from Tu, and I bought one from La. Later, she also talked me into a mouth harp (a small, twangy instrument).

In the jeep back to Sa PaWe shared a Jeep back to Sa Pa from the second village, and made plans to meet later for a weekly show of H'mong music. It was held in a bar called the Green Bamboo, and we arrived early to get a good seat. The place ended up packed, each group of tourists with their own H'mong friends.

We saved a seat for La, who arrived with Tu just before the show started. To our surprise, they each gave us an embroidered friendship bracelet. They began to tie them on our wrists, and our first instinct was to worry about how much they would cost. When it turned out they were free gifts, I was touched.

After some coaxing, La agreed to a Coke, and Steve went to the bar for drinks. The whole rest of the night, La nursed the Coke with utmost care. She left it unopened for maybe 20 minutes, before sipping it ever so slowly. In an unguarded moment, Steve caught her smiling a special secret smile before enjoying a sip.

When we asked, La gave us her address and we gave her ours. She was hopeful, but realistic, and said she would write us once we wrote to her first. (She didn't say, but I would guess other visitors had broken their promises.) Steve offered to send her a disposable camera so she could take pictures and send them back to us, and the idea appealed to her. We just sent her a letter today. We're curious to see what happens to her when she grows up - will her rebellious streak continue? Or will she follow in the footsteps of her ancestors?

( 01~26~02... We wrote to La three times, but we never received a reply. )